Rights of Passage

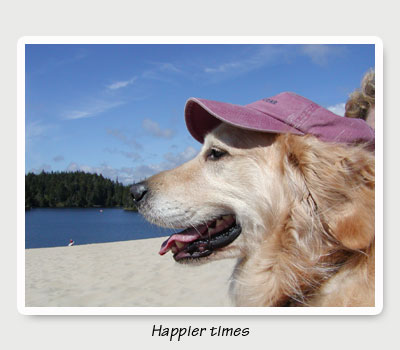

Riley has cancer. Bone cancer, the vet says, in the left hind leg. Just weeks ago he was chasing seagulls on the beach, wrestling the boys in the living room, tugging at his leash all the way to dog park. He’d been stiff lately; sometimes he limped, but we thought it must be arthritis. He is almost nine. Then last week up at the pass he was hit by a sled. A minor collision, but afterwards he could barely take a step.

The x-rays showed spots of crumbly white where the other bones were solid, and now, six long days later, the experts in Portland concur. Osteocarcinoma, they call it. It’s in an unusual place: at the top of the femur where it nests into the hip socket. Too high up to amputate, too far along for treatment. Golden Retrievers, it turns out, are prone to cancer.

All week we’ve stayed by his side, stroking away whines, offering treats and pain pills embedded in cheese. When he sleeps, we sneak away to make dinner or take a shower until he wakes, barking little anemic yips that bring us running back. It’s like having a newborn in the house again, without the joy.

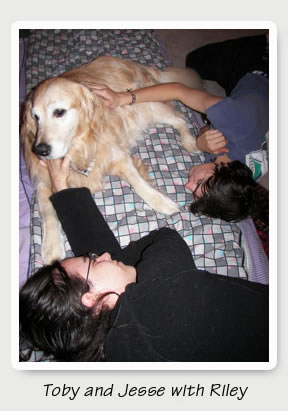

On New Year’s Day, our grown son Toby came over. He and his brother lounged on the floor and reminisced about Riley as a pup. “Remember when I trained him to pull down your sweat pants on command?” Toby asked. On New Year’s Day, our grown son Toby came over. He and his brother lounged on the floor and reminisced about Riley as a pup. “Remember when I trained him to pull down your sweat pants on command?” Toby asked.

“Yeah,” Jesse laughed. “And how he used to do the Piggly Wiggly dance with his bed before he got fixed? Was I the only one who really thought he was dancing?”

It struck me then: Riley is the last Family Dog. With Jesse moving out this summer, any other dog Kate and I get will be the Parents’ Dog.

With the radiologist report in hand, we know what we’re supposed to do. The decision should be clear. Our dog is lame, in pain with a terminal condition. He’s not going to get better, only worse. Putting him down is the humane thing to do. Right?

We aren’t ready for this. It’s all too fast. He’s not even old. Kate waits for me to say the words, but I can’t. My voice hovers over a quagmire of clashing convictions and uncertainties.

There’s nothing simple about euthanasia, no matter how logical or legal the choice.

~

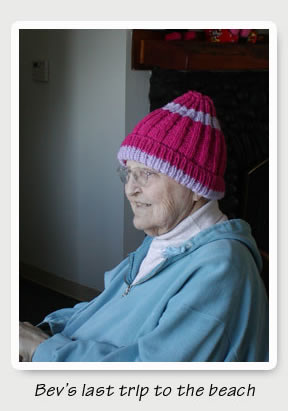

This is our second death watch this year. Last spring, Kate’s mother died of ovarian cancer. Bev was a fervent supporter of the right to end your own life peacefully and was proud to live in the first state to legalize physician-assisted suicide. The last check she wrote, the day before she died, was a donation to Oregon’s Death with Dignity Foundation. “When the time comes,” she said, “There’s no sense in dragging it out.”

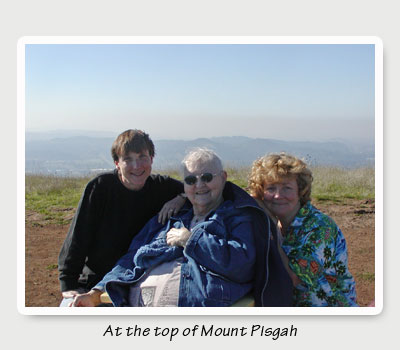

But the truth was, she never stopped fighting for life. It was like the terminal diagnosis propelled her into high gear. That first year, she scheduled her chemo around a surge of travels. Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. By the second year, she only bothered with the wig on special occasions, and if she got too hot singing in the church choir, she’d whip it off and use it as a fan. When she became too weak to walk, she bought a three-wheeled scooter over the Internet and used it and the bus system to get around town. But the truth was, she never stopped fighting for life. It was like the terminal diagnosis propelled her into high gear. That first year, she scheduled her chemo around a surge of travels. Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. By the second year, she only bothered with the wig on special occasions, and if she got too hot singing in the church choir, she’d whip it off and use it as a fan. When she became too weak to walk, she bought a three-wheeled scooter over the Internet and used it and the bus system to get around town.

During the third year, Kate and I were brought her meals daily, but she still managed to swim laps at the pool three times a week. She used Ride Source to get to doctor’s appointments, lunch dates with friends, to church and the opera. The shaky voice on her answering machine said, “I’m out doing fun things…”

Long after the writing on the wall was clear to the rest of us, she jousted death with quixotic effort. Pressed on with one chemo cocktail after another until finally the doctor said, “There’s nothing more I can do.”

Bev begrudgingly let Hospice set up a hospital bed in her living room. That would have been a good time, I suppose, to fill out the Right to Die forms, but she held onto hope. She could still take Ride Source to the opera and go swimming with an aide. It was never too late for a miracle.

It wasn’t until her last doctor’s visit that she finally accepted her fate. Her belly was swollen to triplet proportions, and the weekly peritonesis to drain the cancer byproduct was giving her little relief. No more joking with her favorite nurses: Get me down to twins at least. Bev lay shivering under a warmed blanket, powder-white skin draped like silk from her bones. Her face had adopted unfamiliar features: a sharp, ridged nose that looked nothing like her own, her hallmark apple cheeks now eclipsed hollows. It scared me to see her like that, such a change just from yesterday. Kate gulped back tears and touched her mother’s shoulder. Bev gave a weak smile in return, eyes that glinted with a sad secret.

The doctor rubbed Bev’s leg through the blanket. “We’re down to the last week. Maybe two.” For a minute, Bev looked like she might argue; then tears dripped down the sides of her bald head. Only then did she give in. She gave Kate’s hand a pat, reached for mine, and nodded. Okay, then. And she went home to die. The doctor rubbed Bev’s leg through the blanket. “We’re down to the last week. Maybe two.” For a minute, Bev looked like she might argue; then tears dripped down the sides of her bald head. Only then did she give in. She gave Kate’s hand a pat, reached for mine, and nodded. Okay, then. And she went home to die.

It was too late now for assisted suicide. The forms take three weeks to process. But if she regretted not having made arrangements earlier, she didn’t say so. She set about dying with the same no-nonsense determination she’d applied to living. She called her closest friends, paid her final bills, and made sure the cats would have good homes. Forty-eight hours later, she was gone.

That last day, Kate and I were alone with her. Her lungs rattled with fluid. She labored to breathe. The Hospice nurse had left ample morphine, with strict instructions on how often to use it. It was enough, I suppose, to ease her over. Neither of us spoke of it, but if things got worse, if Bev gave any indication that she wanted me to, I think I would have helped her on. It was too hard to listen to that gurgling breath, like a fountain low on water, to watch her twist and moan. It was a slow drowning, and the nurse said it could go on for days.

Thankfully, she calmed by noon. Still breathing like a dentist’s suction, but more relaxed. I leaned in close. “Are you scared?” I whispered. She opened her eyes in a quick startle, then closed them again with a smile, rolling her head no. Her hand lifted off the bed, wavering in the air until I met it with my own.

Those last hours warped into days. She fell into a deep sleep that I hoped lifted her from her body’s struggle. Kate cried. I both prayed for and dreaded the end, wanting her free from this, us free from this, and still wanting her here. I’d already forgiven myself for the flurries of impatient thoughts and wishes, petty gripes cullied over these years of giving care, but they flew back at me now, slapped me with an overpowering ache. I knew then just how much I was going to miss her. Those last hours warped into days. She fell into a deep sleep that I hoped lifted her from her body’s struggle. Kate cried. I both prayed for and dreaded the end, wanting her free from this, us free from this, and still wanting her here. I’d already forgiven myself for the flurries of impatient thoughts and wishes, petty gripes cullied over these years of giving care, but they flew back at me now, slapped me with an overpowering ache. I knew then just how much I was going to miss her.

You could hear the liquid rising in Bev’s lungs, closer to her throat, and her back arched once with a small gasp. I felt so helpless, able only to sit and watch. It’s so unnecessary, I thought, this elongated discomfort. If she’d filled out the papers like she’d talked about, she could have done this on her own terms, with her own timing. We could have spared her this.

But honestly, as much as she valued her right to choose, I’m not sure she would have asked, in the end, to hasten things. She was a tough bird, courageous as they come. And proud, I imagine, to be making this journey without help. I’m fine. I could almost hear her. I can do it.

As it turned out, the timing was her own after all. She hung on until her grandsons arrived, as I had promised they would. “The boys are here now,” I said. Red-eyed, we circled the bed. “We’re all here. You can go.” One last, deep breath, and she was still.

~

Riley’s head is broad and silky under my hand. I smooth his ear and push my face into the soft ruff of his neck. His tail thumps the carpet. What does he think of this sudden outpouring of attention? This endless supply of rawhide chews? Does he have any sense of his fate, or does he only know it hurts to walk?

I wish I could read his mind. It’s hard enough to consider enabling someone else’s decision to end their own life. But to make that choice for another being, one whose means of communication is limited to wags and licks and subtle eyebrow twitches… how can you know what is right? I wish I could read his mind. It’s hard enough to consider enabling someone else’s decision to end their own life. But to make that choice for another being, one whose means of communication is limited to wags and licks and subtle eyebrow twitches… how can you know what is right?

Maybe, for him, what he’s got right now is fine. As long as he can hobble out to the front yard to pee, and watch squirrels on the deck through the glass door. Ask him and he might say, “Hey, things around here are just getting good. Beef jerky on demand, and what’s this canned food you’ve been holding out on me? It’s one big petting orgy here, everybody treating me like I’m The Dog, when just a month ago, they’d yell at me to shut up if I tried to join in on the conversation. No, man. I’m good. Just keep those pain pills and biscuits coming, and I’ll duke it out with death till the end.”

But he’s not the one to decide. It’s up to us, who have barely slept in the last seven nights. Waking when he whimpers, Kate and I take turns lying by his side until he’s quiet. Even then I can’t sleep. The room expands and contracts with his wheezing.

I want the decision to be for him, to spare him suffering, not because I’m too tired to make it through another night, or because winter break is almost over and we’ve got to get back to work, or because he’s starting to dribble pee on his bed. But all the reasons are entwined; you can’t separate them out like that.

It would be easier if his suffering was constant, but during the day he often seems content, even happy. Yesterday he limped up to the top of the driveway and stood there, nostrils twitching, eyes squinting in the sunlight. I couldn’t coax him back in. He let out his tongue when he smiled, and I didn’t have the heart to insist. I dragged out a lawn chair and we sat there together, faces lifted to the rare winter rays. Neighbors slowed their cars and gave quizzical waves. The mailman pulled up and handed me a bundle. “Best dog on my route,” he said with a firm pat. No one guessed that this huge, regal beast with the lopsided smile was devouring the last precious hours of his life. It would be easier if his suffering was constant, but during the day he often seems content, even happy. Yesterday he limped up to the top of the driveway and stood there, nostrils twitching, eyes squinting in the sunlight. I couldn’t coax him back in. He let out his tongue when he smiled, and I didn’t have the heart to insist. I dragged out a lawn chair and we sat there together, faces lifted to the rare winter rays. Neighbors slowed their cars and gave quizzical waves. The mailman pulled up and handed me a bundle. “Best dog on my route,” he said with a firm pat. No one guessed that this huge, regal beast with the lopsided smile was devouring the last precious hours of his life.

“What if by putting him to sleep, we’re robbing him of some natural process that we don’t know about?” I ask Kate. “Something that’s essential to his transition to the other side?”

Kate thinks a minute. “Like natural childbirth?”

“Kind of,” I say.

“Well, do you feel more enlightened having birthed Toby naturally than, say your sister having a Caesarian? Do you think Toby’s any better off than Heidi?” Of course I don’t. I guess all in all, it doesn’t matter how you get there.

“But what if Riley’s like your Mom?” I say, “And no matter how much he suffers, he wants to wring every last drop of living from his life? What if he doesn’t want us to make it easier for him – that that’s really just an excuse we make up for ourselves? That it’s really about making it easier for us because we can’t stand to see him suffer?”

Kate has no answers, and if Riley does, I’ll never know. We can only do what logic deems best and drag our reluctant hearts along.

Kathy and Ron are friends as well as vets, and they come to our house on a rainy Friday night. It was Kathy who helped us eight years ago, when we had to put our last dog down. Jesse ambushed her in the driveway that day with a water pistol, determined to fend off “Dr. Death.” He bends over now to hug her. “I promise I won’t fight you this time.”

Tonight Riley has feasted on beef stew and buttered bread, followed by an ice cream cone. For a while his old exuberance kicked in, and when Toby came over, Riley met him at the door with happy barks. But for the last hour, he’s been quiet. We gather on the floor around him.

He knows something’s up. When Ron reaches for Riley’s leg to put in the IV, Riley twists his head around to look up at Jesse, who is crying. For a moment, I think he will struggle, but he lies back down and his breathing slows. By the time Kathy asks if we’re all ready, Riley appears to be sleeping.

I couldn’t tell when his breath left him. He just stayed in a perpetual sleep.

~

Last week the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Bush administration’s attempt to overthrow Oregon’s Right to Die law. I gave a victory sigh.

I can’t know for sure what’s right. How can any of us who have not been through it? And then it’s too late. But it seems only fair that we give ourselves the right to make the same decisions we make for our pets. It’s a decision I never want to have to make for myself, but I feel better knowing the option is there. And when my time comes, I hope I have half the chutzpah of Bev, all of Riley’s trusting grace, and a circle of those I love around me.

© Jennifer Meyer. To reprint, please ask

for permission.

Back to Essays

Bev's Website

Riley's Website

|