Boy Tears Boy Tears

My teenage son had a crying spell last night. Not an unusual thing for girls, friends with daughters tell me. An argument or missed phone call triggers an outburst, and they recount a day’s worth of faux pas and petty humiliations that make life at this moment unlivable. They heave their misery like poisoned food, loudly, dramatically, desperate to purge until there is not one tear left. And then, dawn breaks over a new sky, and there is hope again. It’s like that, their mothers say, several times a week at worst.

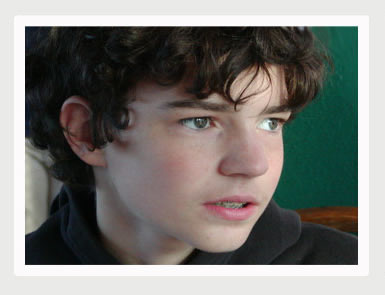

I only have sons. They are sensitive, for boys, and can be emotional. But when adolescence descended on them, it came with a blackout curtain. And the worries and wonders they used to share at bedtime became private matters.

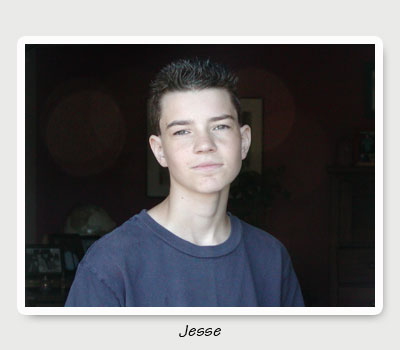

Boys are easier, I hear, as teenagers. Less histrionic. More independent. Steadier. That’s true, I think, from my one-sided parenting experience. But it’s deceptive, this face of self-containment. From all appearances, life is good. My son gets passing grades. He has a delightful girlfriend whose presence softens him. He actually enjoys school for once. He mountain bikes with buddies on the weekend and comes home mud-splattered and endorphin-charged.

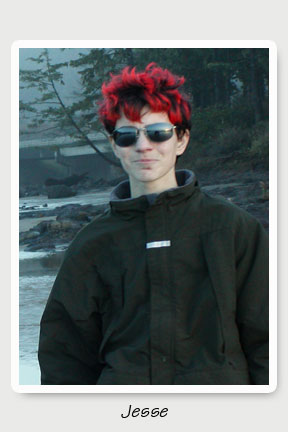

But there’s a bravado to him now. He carries it like a polished shield. I see him pumping it up in the car ride to school. The leather jacket. The spiked cherry-red hair. The earrings. The slouch. The tight jaw. All accoutrements to the image he hones. His voice is deeper when he grunts goodbye. But there’s a bravado to him now. He carries it like a polished shield. I see him pumping it up in the car ride to school. The leather jacket. The spiked cherry-red hair. The earrings. The slouch. The tight jaw. All accoutrements to the image he hones. His voice is deeper when he grunts goodbye.

I imagine high school as a mass of projected self-images, sparring and jostling in the halls, desperately shielding the ghost children behind them. Newly sprouted fears and insecurities are snatched like plunder if exposed. It’s a matter of survival, regardless of gender, to get through a day ego intact. We all did it, growing up. With luck, by senior year you’ve found a niche. An interest, a passion — or if nothing else, a clique — to foster confidence and growth. You come out the other end with a stronger sense of self.

My son is just a freshman, struggling with the hardest part. Trying to figure out who it is he wants to be seen as, before he can get to the part about who he really is. And I don’t get to help. At least not in ways I normally consider helpful. Questions are considered intrusions, embraces are assaults, family time a bore. I’ve learned to give him a wide berth and take the openings when I see them. I feel gratitude for the smallest things: a smile flashed my way at the funny part in a video, an unexpected hug while I make dinner, an unprompted thank you. Mostly, I simply have to take at face value the side he shows to me, because the rest is inaccessible.

But last night he called out from his bed where he lay crying, unable to stop. He held out his arms and clung tight like he hasn’t for years. An earring had started it. A garnet stud swirled down the bathroom drain. It triggered an avalanche in him that stymied us both.

“Is there something else?” I asked. “Something that’s been bothering you? What’s going on?” “Is there something else?” I asked. “Something that’s been bothering you? What’s going on?”

“I just need to cry,” he wailed. “I need to get it all out. It’s not fair how I never get to cry anymore. All day at school, I walk around holding it in.”

I thought he liked school. “Is it that bad? Is someone hurting you?” I envisioned a bully by the lockers twisting his arm, gangs of ruffians surrounding him at the bus stop after school. What undisclosed maliciousness had been tormenting him?

“No, it’s not any thing. Just the way it is. You have to be tough all the time. If you start to feel something that isn’t cool, you have to hide it.”

I remembered how upset he’d been when his class watched a movie that showed wild animals being killed and someone in the room had cheered when the elephant was brought down. How furious he’d been when a classmate once suggested that all retarded people should be euthanized.

He let out a long, thin wail and rolled his head from side to side. “It feels like a balloon getting blown up inside of me. All these feelings. I can’t ever let them out. Not with my friends. And at school, you’re dead meat if you cry. Even if you’re really hurt bad.”

I t’s true. High school is a cruel Darwinian society, and the weakest are smeared. I remember seeing a boy taunted to tears in my own high school, and it was like watching someone being handed a death sentence. Everyone knew. There was no coming back from this. I didn’t know what to tell my son, except, “You’re right. You have to hold it in. But when you’re home and safe, let it out, and we’ll be here with you.” t’s true. High school is a cruel Darwinian society, and the weakest are smeared. I remember seeing a boy taunted to tears in my own high school, and it was like watching someone being handed a death sentence. Everyone knew. There was no coming back from this. I didn’t know what to tell my son, except, “You’re right. You have to hold it in. But when you’re home and safe, let it out, and we’ll be here with you.”

I remembered him coming home the previous weekend, his leg bloody from biking. A friend was with him, and he brandished that sheared shin like a trophy, bragging about how deep it cut and how little it hurt. Only after his friend left would he let me bandage it. He swung his leg up on the kitchen table, still full of swagger and talk. And I thought how far he had grown from the little boy who wanted kisses and a Jurassic Park Band-Aid for every little scratch and bruise. Growing up, I’d thought. Tougher than me now.

But last night I was grateful for the chance to hold him again. To pat down his stiff, red hair and wipe his tears. To feel the bird-thin bones beneath new muscle and realize, My God, he’s still such a kid.

You forget, when they peer smugly down on you from gangly new legs. They bang their way around the kitchen making meals you never knew they could cook. They can get themselves all around town without asking for a ride. They don’t come to you for advice, and they snap at you if you offer it. It’s easy, then, to think you’ve reached the downhill part, that most of the lessons you’ve taught already, and this is your time to coast. You leave him alone when he doesn’t want to talk and believe him when he says he’s okay. You remember things you forgot to do, like learn Italian and write a book. And you think that maybe the time has come at last for you to focus on yourself and your child-weary partnership.

But really, this is the trickiest part of all. They want you there, right next to them, when they need you -- knowing all the right things to do and say. And then, poof! The distance barriers inflate like a couple of passenger airbags, and you find yourself dumped on your ass, wondering what it was you said or did. I’m left navigating a million double-messages, trying to distinguish real boundaries from false fronts, poking the ground for hidden passages. I stumble against my own needs and insecurities, never sure how my advances will be received. But I’m the mom, and it’s up to me to read the signals, take the chances, and absorb the blows if my timing was off or the angle was wrong. But really, this is the trickiest part of all. They want you there, right next to them, when they need you -- knowing all the right things to do and say. And then, poof! The distance barriers inflate like a couple of passenger airbags, and you find yourself dumped on your ass, wondering what it was you said or did. I’m left navigating a million double-messages, trying to distinguish real boundaries from false fronts, poking the ground for hidden passages. I stumble against my own needs and insecurities, never sure how my advances will be received. But I’m the mom, and it’s up to me to read the signals, take the chances, and absorb the blows if my timing was off or the angle was wrong.

No doubt he will come home from school today more gruff and disinterested than ever (just to make sure I don’t get any ideas about last night). But I’m reminded now that behind that fifteen-year-old façade, my child still lingers, and no matter how deftly he dodges connection, he still counts on me to know when to come in there after him. And as much as I hate that he has things to cry about, I love that he still cries.

© Jennifer Meyer. To reprint, please

ask for permission.

Back to Essays

|