|

Blindsided

I blamed myself for having given in to the gun in the first place. My partner, Kate, and I had managed to raise one peace-loving boy whose only inclination to shooting things was in an occasional video game. But our younger son’s quest for guns started as a toddler, and his childhood was a timeline of arsenal acquiesces. Just squirt guns to start, moving on to Nerf guns, noise-happy laser guns, eventually cap guns and finally at twelve, the coup d’état: the air-powered BB rifle. Each one wrested from my better judgment by a doggedness that sucked all my reserves dry. Jesse was not a boy to take “no” at face value.

As it turns out, it didn’t really matter what we believed. Because in the end, it was another boy’s gun, in another boy’s house, fired by yet another boy. A boy whose parents had managed to stick to the no-gun policy but had failed, apparently, in teaching the primary rule of gun play: Never, ever point at someone’s face.

It was Christmastime, and Kate and I were cooking dinner for a small group of friends. I was in a generous, holiday mood, so when Jesse’s friends, Matthew and Tyson, stopped by, I invited them to stay. I made a second pan of lasagna and asked Matthew’s mother to join us. After dinner, the boys walked up the street to Matthew’s house to hang out. They were fifteen now, beyond the need of constant supervision.

We were sitting around the fire, opening presents, considering a game of Cranium, when the boys burst in the front door. Jesse’s hand was clamped over his left eye. “Okay, people. We’re going to the hospital,” said Matthew, his newly deep voice full of bluster.

Jesse’d been shot in the eye, they said. It took a minute for the words to sink in, for me to grasp that this was more than a stunt or the kind of dramatic hype these boys revel in. “Let me see,” I said, nearly tripping over Riley, who was barking and circling the group.

“No. Just take me to the hospital.” Jesse pivoted away from me.

“I have to see,” I insisted. His face was white with shock. When he lowered his hand, it wasn’t the wound itself that jolted me, or even the blood. Rather the ultimate lifelessness of his eye. Glazed over and black. He looked like one of the zombies in his favorite video game. “Okay. We’re going now.” I jumped in the car with him, yelled for Kate to hurry, and charged through the rain to the hospital.

“What happened?” I asked. He shifted to face the passenger window, gave his head a small shake. “Just tell me who shot you.”

“It was Tyson,” he said. “But it wasn’t his fault. He thought it wasn’t loaded.” After a beat, he added, “Maybe it wasn’t. He was really close. Maybe it was just the air.”

I didn’t answer but let that thought carry us the rest of the way. Was that possible? A blast of air strong enough to burst blood vessels? It would be ugly but temporary. I hung all my hope on that thought. And if there were a BB, maybe it had bounced off. Hit at an angle and glazed the surface, just damaging the cornea. That’s all.

It wasn’t until the ER doctor pointed out the entry wound — a ragged hole in the corner of Jesse’s eye — that I let the truth creep closer. It wasn’t until the CAT scan came back — showing braces, an earring, and a solid sphere in the back of an eye socket — that I allowed myself to envision what had become of the BB Tyson had shot.

The ER nurse gave him morphine in an IV, and the story finally tumbled from him. They’d been playing foosball and video games. Jesse’d gotten Matt’s gun from his room and with what I’m sure was aggravating authority, aimed and shot around the room and, he eventually admitted, at Tyson’s feet. He was “dry-firing” it, he said, which means he only half cocked it so no BB’s actually came out. He’d set the gun down and had turned his attention to Matthew’s video game when Tyson said, “Hey, Jesse…”

This is the part I imagine over and over again. Tyson’s voice, slow and sultry. A calculating calm cloaking his resentment. Jesse, distracted but captured by Tyson’s tone, swivels in his seat to face his friend. He’s angry, at first, to see the end of the rifle barrel, two feet from his face. But before he can even register the danger, before his anger can convert to fear, before he can yell or reach a hand to push the gun’s barrel away, there is a crack of air, a javelin of pain shooting into his left eye.

Lying in a dimmed room in the ER, Jesse let me hold his hand. With wadded tissue I dabbed at the pink fluid leaking from his eye like tears. I held back my own tears, and I tried not to think of what this all meant. You can’t really, at first. You deal with the moment. You make sure the pain medication is sufficient and the blankets are warm. You rivet your attention to every nurse, doctor, and attendant who comes into the room and you listen carefully to the sparse words they offer. You look for clues to what isn’t being said, but you don’t ask, because you’re not yet ready for the answers.

The ophthalmologist arrived, dressed for Saturday night with a Bond-like briefcase of equipment. He studied Jesse’s eye and he scowled at the x-rays, and in the end, he referred us to the Casey Eye Institute in Portland. It would be faster if we made the two-hour drive ourselves, he said, rather than waiting for an ambulance. The surgeon and staff would be ready for us. He gave us written directions and a number to call when we were a half an hour close.

The nurses helped us set Jesse up in the back of our van with pillows and blankets and made sure he had enough morphine to last the trip. The rain was pounding now, the streets swathed with sheets of water. Were they crazy, sending us shock-ridden parents out on this mission towards further disaster? Surely they had overestimated my abilities, misinterpreted my fear-struck silence as composure. But at least this way we would be together. Fingers clamped to the wheel, I tried to steer my mind away from visions of twisted metal and flashing lights. I set before me my only goal for the next two hours: get us all to Portland safely. On the freeway, I paced myself behind a semi truck and followed its taillights like a prophet.

Sluicing through the rain, wipers throbbing, I felt submerged. Our van a vessel swept along this raging highway river, kept afloat by blind will. Kate’s hand squeezed the hollows of my knee. Jesse shifted in the dark and sighed. Breathe, I reminded myself, as if waking from a dream of swimming underwater. There is air. Breathe it.

It was 1:30 before we arrived at the Eye Institute. We spiraled up through an empty parking structure to the fourth level, where the assistant surgeon met us at the door. We followed him through darkened hallways to the operating area. Nurses were waiting with a nightgown, slipper socks, an IV, and blood pressure cuff. The anesthesiologist explained to Jesse how the gas would make him sleep and he would wake up when it was all over. Then the head surgeon arrived in an elegant black turtleneck and gray pleated trousers, looking like he’d stepped out of a Ralph Lauren photo shoot.

He examined Jesse’s eye and told us what he expected to do: enter the eye through two small incisions on either side, extract the BB, access the damage, make any repairs he could do at the time, then stitch up the incisions and the entry wound. He warned us that the damage was likely to be extreme, that there was only a 30-40 percent chance that he would retain any vision at all in the eye.

As they wheeled him away, the team engulfed him like a school of fish. We stood there a moment in the deserted pre-op area, clutching the blankets we’d bundled Jesse in. Eventually we found our way to the waiting room and, like obedient kindergartners at naptime, took off our shoes and lay down on the narrow cushioned benches.

Kate fell immediately into a deep merciful slumber, but I couldn’t even flirt with sleep. Bright fluorescent lights filled the empty room with a cheeriness that seemed obscene under the circumstances, but there was no visible switch to dim them. One glassed wall offered what would be an incredible view in daylight, and a door to an open-air terrace. I stepped outside in my stocking feet, only vaguely aware of the cold, of the wet soaking into my socks. The rain had stopped and moisture lifted from the valley below in rising mists. A full moon darted behind roving clouds. Wind stirred through the tops of firs, and I crossed my arms against the chill. It was beautiful here, in these wooded hills above Portland. I tried to open my senses and take it all in: the rain-fresh air, the twinkling lights below, the storm-ridden sky. But nothing touched me. Beauty I would normally find inspiring or soothing bounced off me like water on plastic wrap.

When the head surgeon came out two hours later, I was slumped in a wheelchair I’d found, rolling myself forward and back in an autistic daze. Kate leapt awake at his voice, and I moved to sit by her. Slipping my hand into hers, I breathed in deep. I knew, I suppose, from the hard line of his mouth, the way he braced his eyes against ours, but I waited for him to say it. The damage was extensive. They had removed the BB but could do little else. The minimal light vision that the eye still retained would probably fade to black over the next few days.

I wondered about depth perception and was remembering a skit I’d seen on “Saturday Night Live” with a man called Mr. No Depth Perception who pours wine on tablecloths and puts his hand through windows, when the doctor’s voice called my mind back to attention. “…Sympathetic eye syndrome,” he was saying, “when the good eye shuts down in sympathy with the injured eye.” The safest thing was to remove the injured eye as soon as possible.

Remove his eye. The very idea took the breath from me. It was so brutal, barbaric. I could only think of a cat I’d once had that lost an eye in battle, and I wondered if they would stitch Jesse’s eyelid shut. If that side of his face would be sunken and flat in a permanent wince. I held up my hand in front of me as if to stop the flow of unwanted information. “Sorry,” I said and closed my eyes for a moment. “I wasn’t prepared for this.”

~

Doernbecher is a model children’s hospital, and our room was a welcoming haven. There was a window seat bed, already made up for us, looking onto a courtyard with whimsical sculptures, play equipment, and trees. It was 6:00, the dark just beginning to ease, and the rain clouds had dispersed. Jesse slept an anesthetized sleep, and Kate and I dozed gratefully on the twin window bed, assured by the quiet bustle of nurses and attendants who kept watch on him.

There is this cushion of goodwill that inflates around you during crisis. Like airbags or shock, it buffers you from the sharpness of reality for a time. The sadness stays there at the back of your heart, and sometimes your mind flits forward to the hardships to come, but there’s this haze that soothes you into a sense of gratitude for everything you haven’t lost. There in that soft-lit hospital room, my heart stretched full with love and thankfulness. Kate’s arm gripped me against her sleeping frame. Jesse breathed heavily, his unbandaged eye fluttering with dreams. All that mattered, I assured myself, is that we had each other.

Jesse’s own cushion of euphoria came later, bolstered by the morphine, no doubt. He slipped in and out of sleep through the next two days. When he was awake, he talked steadily, softly. He felt brave and big-hearted, and he reveled in the magnitude of his own generous spirit. He took a call from Matthew, and his voice went gruff and soft at the same time. “It’s okay… and, hey, tell Tyson I’m not mad, okay? Tell him I won’t let this get in the way of our friendship.”

“When we get home, I want you to throw my BB gun in the garbage,” he told Kate. “And all the toy guns, too. I never want to see another gun again.”

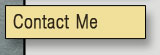

For those two days, that hospital room was our womb-like sanctuary, protecting us from the harshness of the outside world while we prepared to ease ourselves back into it. He wanted us always within reach, so I moved a reclining chair next to his bed. We took turns holding his hand while he rambled on about all the people he loved and the good things he was going to do for them. “I love you, too,” he said when his brother in college called, in a tone I’d never heard him use with Toby before.

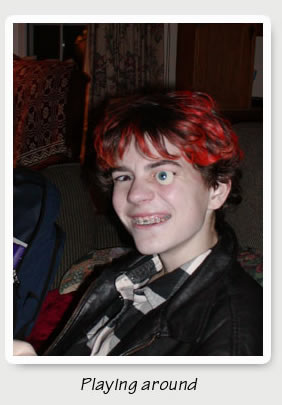

He looked so young and vulnerable in the near-dark, his thin, pale shoulders poking through the slits in his nightgown. The hair he had once dyed and spiked in a bold gesture of individuality now jutted from his head in maniacal red-dipped tufts.

“They can take my eye out if they have to,” he said, “but I want to keep it.” He smiled, egged on by our grimaces. “I’ll put it in a jar by my bed. No, I know: I’ll make a lava lamp out of it.” We groaned as he described how it would float up and down in an iridescent glow and watch over him as he slept.

When we returned home, we were awed to find that dear friends had let themselves into our house. Kathy and Robin had cleaned up after our dinner party, vacuumed and dusted, filled our refrigerator with home-cooked meals, and even set up a Christmas tree strung with lights. Matthew and his mother, Kathleen, had fed the dog and cats and hung a homemade banner welcoming Jesse home.

Over the next several days, there were deliveries of flowers and balloons and baskets of chocolate. Friends stopped by after school for visits. Relatives called from as far as Spain and sent presents and gift certificates. Jesse reigned court from the couch with a jovial air. He described in detail how prosthetic lenses are made and said if he had to have one, he was going to get his name painted across the bottom of it. Then he could introduce himself by saying, “Hi, I’m ___” and tug down his lower lid. Once I overheard Jesse talking with Matthew about how when he tried to see through the damaged eye, all he could see was Tyson’s face and the barrel of the gun. “It’s like the last image your eye sees is burned into it forever,” he said. After a length of silence, Matthew said, “Whoa, dude, what if it had been a naked woman who’d shot you?” And they both guffawed until their laughter gave way to deep thought. “That would be so cool,” Jesse said.

We found a local eye surgeon who thought it was worth giving the eye another chance. The sooner the better, he said, and scheduled the surgery for December 26th. We still had a few days to pull Christmas together. Our older son, Toby, came over with his girlfriend to help us trim the tree. Kate’s mother watched movies with Jesse one evening so Kate and I could do a last-minute power shop and replace all the bike-oriented presents on Jesse’s list with slippers, video games, and a telescope. Toby came with us to Kathy and Robin’s for Christmas Eve dinner, then spent the night in the trundle bed next to Jesse. We filled stockings listening to their murmurs and laughs, and I reveled in this miraculous tenderness between them, after 15 years of embroiled sibling antagonism.

Christmas day itself was a shaky mix of merriment and dread, melancholy and hope. It was wonderful to see Jesse excited and happy and to steep ourselves in tradition and family, but as the day wore on, the next morning’s event was hard to ignore. At dusk, we trudged up hill to the neighbors’ house for dinner. We ate turkey at the kitchen table, but my gaze kept drifting to the family room, my mind replaying the scene as Jesse had described it. Is that where he sat? Was Tyson standing there? Christmas day itself was a shaky mix of merriment and dread, melancholy and hope. It was wonderful to see Jesse excited and happy and to steep ourselves in tradition and family, but as the day wore on, the next morning’s event was hard to ignore. At dusk, we trudged up hill to the neighbors’ house for dinner. We ate turkey at the kitchen table, but my gaze kept drifting to the family room, my mind replaying the scene as Jesse had described it. Is that where he sat? Was Tyson standing there?

We were at the local hospital by midmorning the next day, but it was late afternoon before the surgeon finally appeared in the waiting room. He gestured us into a private consulting room where I had earlier watched a large boisterous family reduced from stoic gaiety to howling grief. I sat forward, elbows on knees, and waited for the news we’d known, on some level, since the beginning.

The BB had ricocheted all around the inside of Jesse’s eye. The retina was shredded. He had worked for two hours doing whatever repair he could, had propped up the retina wall and replaced the depleted eye fluid with a silicon gel that would temporarily keep the eyeball from deflating. There was a very slim chance that some shadow vision would return, but never enough to be useful. Without sight, the eye would eventually begin to atrophy. The next step was enucleation. The eyeball itself would be replaced with a coral sphere, an implant, which would attach to the socket muscles and support a prosthetic lens. The lens would be hand-painted to match the surviving eye. With luck, the disability would be subtle, only minimally restricting Jesse’s activities.

For the first 12 hours, Jesse had to lie face down, his head pressed awkwardly into a donut-shaped foam pillow. He fought waking angrily, as if he already knew the reality that waited for him. His nurse, a small no-nonsense woman with a faded German accent, tried to force him up, insisting he would feel better if he walked himself to the bathroom and ate some dinner. “I’m not hungry!” he snapped back at her, swatting away the tray of cold turkey and stiff gravy. “Just let me sleep.” Finally, she surrendered and gave him enough painkillers to ease him from consciousness. In the warm, darkened room, Kate and I sat in separate chairs. Heavy rain pattered against thick glass. The IV machine purred. At last, I let my own tears fall.

One split second. One imbecilic impulse. And a life’s course changes. The damage is done. There is no repair, no healing that will bring back sight.

The times he is buoyant and his spirit is vibrant, that’s when I relax. I take my cues from him, and I think then that this is only one of life’s inevitable hurdles, and he will sail over it gallantly. It will deepen his character, give him an edge of uniqueness that he will use to his advantage. He will pull through this challenge with a graciousness that will stun us all. And we will be right behind him. The times he is buoyant and his spirit is vibrant, that’s when I relax. I take my cues from him, and I think then that this is only one of life’s inevitable hurdles, and he will sail over it gallantly. It will deepen his character, give him an edge of uniqueness that he will use to his advantage. He will pull through this challenge with a graciousness that will stun us all. And we will be right behind him.

But when he cries, when he lashes out in pain and pushes me away, when he closes in on himself and shuts his heart, I feel the hugeness of this tragedy. I’m afraid that this will be the single event that alters everything. That this is what we will all look back on and blame for his downturn. That this will be the event that robbed him of his future.

The sight did not return, and the pain did not ease. It would be another month before a third surgeon who specializes in enucleation could schedule surgery. It was a month of waiting, of battling searing pain with round-the-clock painkillers — four times the usual dose.

Kate went back to work, and my days were consumed with Jesse’s care: changing bandages, administering eye drops and medication, running to the pharmacy for refills, picking up videos and food requests, making odd meals of anything he would even consider eating. The painkillers killed his appetite along with the pain. He had been skinny before. Now, at 5’5” and 87 pounds, the sight of him was jolting. It made me wince to feel the sharpness of his bones pressed against his stark-white skin.

In spite of the relentless pain, Jesse maintained a strong spirit, at least for the friends and family who still visited. And he steadfastly defended Tyson’s blamelessness. Kate and I didn’t feel so generous. We didn’t know Tyson well, and we had never met his parents. Of course, it was an accident. And surely Tyson suffered his own hellish turmoil. I tried to mirror Jesse’s empathetic bravery, to support his efforts to maintain their friendship. But privately I imagined shaking this brainless boy by the shoulders. Why did you do this? I railed in my mind. What the fuck were you thinking?

It was almost a week after the accident before Tyson’s mother had called, offering her sympathy and suggesting a quick drop-in visit on the way to Tyson’s piano lesson. By then I had worked up a good case of outrage at their glaring silence. I had dreaded talking to these people and didn’t look forward to facing them then, on my own with Kate still at work, but where, damn it, had they been all this time? By all that is right they should have called before this. They should have been on our doorstep with their hearts in their hands, and their homeowner’s insurance policy in their back pocket.

I wanted to hate them. I wanted to see them stand face to face with Jesse’s bandages and pain. I wanted them to feel the utter weight of responsibility and guilt, to squirm with the knowledge that I could sue them for all they were worth. Instead, I found myself liking them, comforted by their teary sympathy. “Don’t even think about the hospital bills,” they said. “Of course, we’ll help.”

But three weeks later when I called to ask about liability coverage on their homeowner’s policy, Tyson’s mother told me they’d decided to handle it themselves. They’d already had several claims against insurance this year and didn’t want to risk a rate raise.

“Do you have any idea how much money we’re talking about?” I asked, incredulous. The hospital and doctor bills alone would add up to nearly fifty thousand. Then there was the prosthetic, which would have to be replaced every few years for the rest of his life, professionally cleaned every six months. Not to mention the more subtle long-term effects: the emotional impact of having someone whom you consider a friend call your name and shoot you in the face. The weeks of physical pain. The loss of a body part.

“Well, you said your insurance covered 80%,” she explained. “So we were thinking we could split that 20% among the three families, since, really, all three boys were equally involved.” It was Matt’s gun, she continued. And Jesse was the one who got it out of Matt’s room and started playing with it. Tyson never would have touched the gun if Jesse hadn’t been shooting it around first.

My mind raced in circles and my mouth went dull. Her son shot my son. Nothing would erase that. Not even if Jesse had handed the gun to Tyson and said, “Shoot me.” My son would be paying for Tyson’s mistake the rest of his life. What consequences had Tyson suffered to carry his share of the pain? I got off the phone quick before the rage took control and I found myself saying something stupid like, “As long as we’re sharing everything equally, how about an eye for an eye?”

Hers was the kind of reasoning a desperate mother constructs to protect her child, and later that week when I told her we had retained a lawyer, I appealed to that same mother logic. “If it were Tyson, you would do the same.” We weren’t going after a fortune, I explained. We didn’t want to attack their assets. We only wanted an insurance settlement that would cover Jesse’s future ophthalmology bills.

As the date for the enucleation approached, visits from friends dwindled and Jesse grew more and more irritable. For three days before his surgery, he holed up in his room, foul-tempered and angry, refusing food or conversation. He batted off concern like insults. “Leave me alone,” he’d snarl if we came near. But the last night before surgery, Kate thought she heard him crying as we were getting ready for bed.

“Shhh,” she said, head cocked, toothbrush in hand. And we both went in. A high, thin wailing leaked steadily from his open mouth, his contorted face barely visible in the hall light. At last, the sorrow was rising.

All these weeks he had been too brave, too forgiving, too optimistic, magnanimous. The darker feelings bubbling out sideways at us, like sparks and gas spewed from a volcano’s flank: irrational exasperation, tense impatience, peevish demands. But always the strong front, the stoic face. All these weeks he had been too brave, too forgiving, too optimistic, magnanimous. The darker feelings bubbling out sideways at us, like sparks and gas spewed from a volcano’s flank: irrational exasperation, tense impatience, peevish demands. But always the strong front, the stoic face.

The crying squeezed from him steady and tight, like air from a balloon with the opening pinched. I don’t want them to cut my eye out of me! We climbed on the bed with him and held him, one on each side, his bird-thin arms wrapped tight around us.

The next morning he rallied and impressed the nurses and staff with his courage and humor. He teased them with a Dr. Zombie action figure he’d brought along for the ride, and he threatened to use the IV plug like a straw to drink his own blood. But that was our last glimpse of the old Jesse for a while. For days after he got home, he lay in his darkened room, groaning, barking out in protest at any crack of light. He woke only to request more pain pills and to ask if any of his friends had called. The answer was always no. After all the fanfare of the first two surgeries, the phone was blatantly silent.

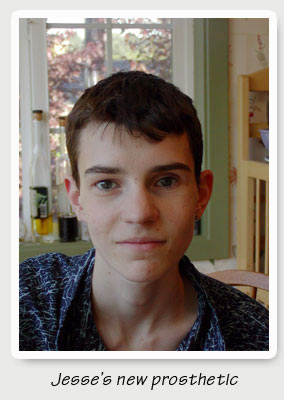

Jesse returned to school in February, fifteen pounds lighter, with a temporary glass prosthetic that tended to stray off to the left. It was a jolting blue, much lighter than his other eye, and the light bounced off of it in a way that was unnatural. But it was better than a patch. Jesse returned to school in February, fifteen pounds lighter, with a temporary glass prosthetic that tended to stray off to the left. It was a jolting blue, much lighter than his other eye, and the light bounced off of it in a way that was unnatural. But it was better than a patch.

He was welcomed back like a hero, and everyone wanted to check out his fake eye. He got kids to pay him a dollar to tap his eyeball with the tip of a pencil. He’d floor unsuspecting students by using his fingertip to rotate the lens back into place when it went off-kilter. Once it accidentally fell out and his friends all agreed he could go trick-or-treating next fall without a costume. At first, the freakishness of it all bought him notoriety, and he fed off his fame. But when the novelty dwindled, he was just a freak.

Jesse’s bravado faded. The friends who had trampled our living room after his first surgery now made themselves scarce. Teachers grew impatient with his resistance to make-up work. He reverted to his middle school tactic of hiding inside a hooded sweatshirt. I watched helplessly as he withdrew further and further into himself. At home, he refused to come to the table for dinner. He watched TV and played his guitar. In the world, he was timid and fearful. He didn’t want to be left alone in the house. He had trouble sleeping, and more mornings than not we’d find him asleep on our floor, cocooned into his comforter. When I looked at him, I saw a ghost. When I looked at him, I saw a broken boy.

Eyes are so much more than organs of vision. They are little portals to our minds, winding a way into our souls. Looking into a person’s eyes opens an avenue of subliminal information. It’s not so much what you see there but the synapses of energy that flow between you. The subtle, reassuring recognition of that person’s presence.

When I looked at Jesse now, I had to fight my way through the magnetic draw of that glassy eye to find the son I remembered. Ah, there he is. Only then could I relax. And if it was this difficult for me, I couldn’t help but imagine how it would be for others. If having a glass eye automatically created a subtle barrier. If there would always be something a little bit askew in his appearance, something that made eye contact with him discomforting.

~

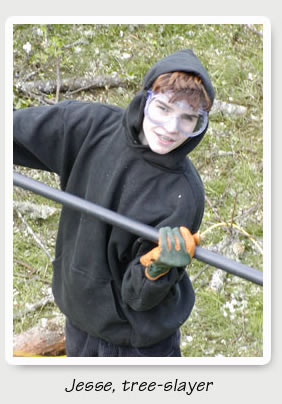

Last week, heavy spring rains and gusts toppled a 35-foot apple tree in our back yard. It was the kids’ tree. It still held the frayed rope from the tire swing I had set up for them over a decade before and the rotting plywood and crooked 2x4’s that Jesse had hammered up himself, refusing assistance on his very own tree fort. The boys’ old playhouse, now a shed for outgrown bikes and  skateboards, was crushed. It was as though the boys’ very childhoods lay crumpled in the backyard, adorned by a smattering of sadly hopeful blossoms just starting to burst from the limbs. skateboards, was crushed. It was as though the boys’ very childhoods lay crumpled in the backyard, adorned by a smattering of sadly hopeful blossoms just starting to burst from the limbs.

We bought a 10-inch chain saw on a pole and determined to save money by cutting back and hauling away as much as we could ourselves.

Jesse lit up at the sight of it, and my mother-panic shifted into gear. Of course he had protective goggles, gloves, and boots, but I flitted around him like a nervous finch. “Watch your feet. Look out. That could fall on your head.” More than ever these months, I had become acutely aware of lurking mishaps. I wished he would just step back and let me do it, but it was a mission of his, the dismantling of this tree, and I hadn’t seen such motivation since before the accident. He laughed and joked between fellings. Roared as he lay into an impossibly thick limb. Whooped when it fell with a reverberating thud to the ground.

By the fourth day, he had proved himself to be a competent chainsaw operator and I had stopped hovering. He was down to the trunk now and had mastered V-cuts to get through the foot-thick pieces. I watched from the deck as he worked with determination and confidence, and I reveled in the new Jesse that was emerging, at last, from his brittle shell. Riley galloped in maniacal figure eights around the brush heap and firewood stack, barking hysterically and stealing wood chunks. By the fourth day, he had proved himself to be a competent chainsaw operator and I had stopped hovering. He was down to the trunk now and had mastered V-cuts to get through the foot-thick pieces. I watched from the deck as he worked with determination and confidence, and I reveled in the new Jesse that was emerging, at last, from his brittle shell. Riley galloped in maniacal figure eights around the brush heap and firewood stack, barking hysterically and stealing wood chunks.

“Look at him, Mom!” Jesse fell to his knees laughing when Riley pranced away with his jaw around a log as thick as his head, his neck barely able to hold up its weight.

“You must be proud of yourself,” I said that night during our ritual hot tub soak.

“Proud,” he said, “and sad.” His bottom lip puckered. “I loved that tree.”

I loved it, too. And all the memories it held. I hate the obscenely empty space that’s left, framing our neighbor’s less-than-picturesque backyard and roof. The yard looks ravaged now, the lawn a matted bed of mud, sticks and sawdust, the playhouse a crumpled ruin. But what’s done is done, new things will grow, and life goes on.

~

Today, Jesse got his permanent prosthetic lens put in. This one is molded exactly to the shape of his eye socket and the paint job is an unbelievable match. It moves, like magic, in sync with the real one. He was grinning triumphantly when we dropped by Kate’s workplace to show it off. He pushed his sweatshirt hood off his head and challenged Kate’s coworkers to identify the real one. “Watch it move,” he instructed them, and slowly looked right and left, then quickly crossed his eyes and laughed. Today, Jesse got his permanent prosthetic lens put in. This one is molded exactly to the shape of his eye socket and the paint job is an unbelievable match. It moves, like magic, in sync with the real one. He was grinning triumphantly when we dropped by Kate’s workplace to show it off. He pushed his sweatshirt hood off his head and challenged Kate’s coworkers to identify the real one. “Watch it move,” he instructed them, and slowly looked right and left, then quickly crossed his eyes and laughed.

At last, he looks like himself again. But it’s not just the eye that’s different. An enormous anxiety has lifted from him. It is as if all these months, Jesse has been holding himself back for this moment, waiting to see if his life can be normal again. And I suppose, in a way, I have, too.

There’s this feeling that comes after a tragedy. An acute sense of the fragility of life and a separation from the rest of the world, who all seem so naïve and unaware, blithely stepping off curbs as if the possibility of being run down by a truck didn’t exist. It’s all so enormously precarious, life. You think it’s solid, but the ground you walk on is ice. It can crack any time. And when it does, the momentum or faith or distractedness or whatever it is that glides you blissfully blind through your days gives way, and all you can see is the churning, frigid waters at your feet.

For months now, I’ve kept watch on that subterranean tributary, unnerved by life and all its inevitable hardness. But something has shifted. When Jesse laughs, a lightness moves through all of us. There’s a distinctive steadiness to the ground below my feet. I haven’t forgotten that the water is there, but I’ve remembered that I can swim.

© Jennifer Meyer. To reprint, please

ask for permission.

Back to Essays

|

|