|

||||||

|

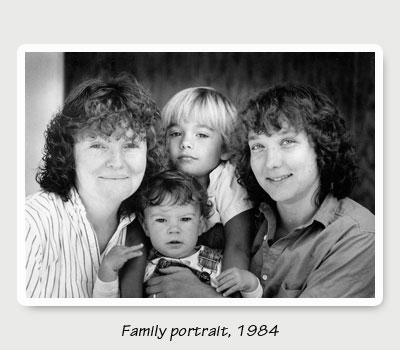

Domestic Warriorby Jennifer Meyer When Kate and I decided to have a baby back in 1982, we knew there were people who would consider that act alone a form of child endangerment. My own mother asked how I could subject a child to our lifestyle. She changed the subject whenever I talked about my pregnancy and declined an offer to come visit her first grandchild. In public, smiles offered at my bulging belly quickly changed to smirks when Kate would take my hand. There was no question of what we were up against. These were the days of Anita Bryant’s crusade to “save the children” from the very likes of us. But in the eyes of the law, she wasn’t my wife, and we’d had no gathering of family and friends to launch us joyously into our life together. We were denied family housing at the university Kate attended because we weren’t married. Denied family insurance. Denied family membership at the health club. Kate would never have access to the social security money I, as sole breadwinner, was socking away. And only by the willingness of staff to bend rules was I allowed into Kate’s hospital room when she gave birth to our stillborn son, or she into mine when I had a hysterectomy. Schools and doctors stretched their definition of family to accommodate ours, but until 1998, when we were finally allowed to jointly adopt each other’s birth child, we were, by law, two single mothers cohabitating. We knew all this from the start. We had chosen to live our lives on the fringe of society. Not that being gay was a choice, but living openly as lesbians was. Having children was. Second-class status was the price we had to pay, and for the most part, we took it in stride. We were stroller activists, letting our mere visibility put a friendly face on the unfamiliar. What I never dared to expect was that by the time I turned fifty, I would be able to legally marry my life partner. That the largest city in my own Northwest state would be right behind San Francisco on the frontlines of the same-sex marriage revolution. It’s a funny thing, getting married now, quick before we can’t. How many couples weren’t quite ready to seal their commitment, or were in the midst of a rough spot? God knows Kate and I have not always been poised for the plunge. But now was perfect for us. Having just sent our youngest away to school, we were relishing life as a twosome. I was ready, eager, and my heart soared. Nothing could dampen my happy day. Not the rain, not the lines, not even the hoarse protester dressed in camo fatigues screaming, “One man! One woman!” over and over. When we finally reached the tables where people filled out forms, Kate handed me the pen. “Your handwriting’s better.” I was thrown momentarily by having to decide which of us was the groom and which was the bride, but I’d crossed out “father” on forms for so many years, I didn’t think twice before printing my name under “groom.” Later Kate complained, “I wanted to be the groom.” By 1:30, we had our license in hand. We drove across Hawthorne Bridge and followed directions to Keller Auditorium where volunteer ministers, rabbis, priestesses, and monks were performing marriage ceremonies for free. It was Friday afternoon. By Monday there could well be an injunction. There was no time to stop for the bridal bouquet Kate dreamed of. In the parking garage, Kate climbed into the back seat of the Honda and we changed into the wedding clothes we’d brought. Kate had a white lace dress, purchased the week San Francisco opened the doors of City Hall to gay couples. In my typical fashion, I’d put off thinking about what to wear until the night before, then gave myself an allergy attack plowing through the dusty corners of my closet. I emerged with a pieced-together, baby-butch outfit from the eighties that looked more like a Halloween costume than wedding attire. Fortunately, a good friend — who is not only an excellent dresser but also my size — gently directed me to an elegant black pantsuit of her own. Back in line, we checked our watches and peered up the stairwell. “Relax,” I assured Kate. “It’s only one more landing. We’ll make it.” Children swung on the railings and blew bubbles. One man in a tuxedo made business calls on a cell phone while family members fussed over his partner. People cheered each time a newlywed couple came back down the stairs. The men in front of us asked us to be their witnesses and offered to be ours. When our time came, we opted for the first available officiate — a Lutheran minister who had driven down from Washington to attend a press conference and was so inspired by what she’d heard that she came over to help. Daniel and Matt were her first couple. It was foolish, I suppose, to believe that doors nailed shut for centuries would swing wide open. Even so, I wanted to scream, to hire lawyers, to take to the streets with banners. It was unexpected, this sudden gift of status. But now that I had it, I knew more than ever what I’d been missing. I never thought a piece of paper would have such an impact on my life. After all, we’ve been skirting societal approval for decades. But there’s something huge here, and it’s not just about human rights. It feels different. When I look into Kate’s eyes and see our lives stretched out together. When I reach for her hand across the table without glancing around the restaurant first. When I check the box next to Married on a medical form. We got married. And it turned out to be so much more than a political act. © Jennifer Meyer. To reprint, please ask for permission. Update: Our legal marriage lasted not quite year, at which point Oregon voters decided that same-sex couples should not be able to marry after all. All 1,700 gay and lesbian marriages in Oregon were annulled with a letter from the governor and a check refunding the $60 license fee. In 2007, the Oregon House of Representatives passed a bill allowing same sex couples to register in a "civil union" partnership. This bill went into effect February 4, 2008. Kate and I were there that day, in line once again to legalize our relationship. For a photo slideshow of that day, click here. Update to the Update: Although gay marriage was still illegal in Oregon, Kate and I drove up to Washington in November 2013 and were legally, officially, irrevocably married in the home of friends on Whidbey Island, this time with our kids present.

|

|||||

|

||||||

We didn’t care. We were young and in love and willing to take on the world. We would cushion this child from society’s hatred with a circle of love. Better yet, we would change the status quo. And in small ways, we did. By the time Toby was one, my mother realized we weren’t such bad parents after all. By the time Jesse was born, my brother was introducing Kate as my “wife” at his wedding.

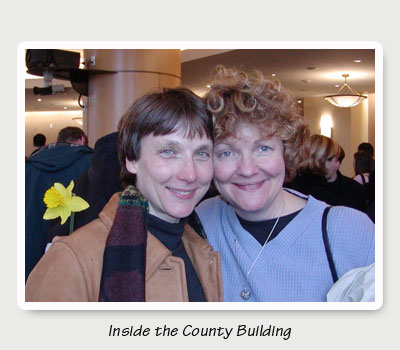

We didn’t care. We were young and in love and willing to take on the world. We would cushion this child from society’s hatred with a circle of love. Better yet, we would change the status quo. And in small ways, we did. By the time Toby was one, my mother realized we weren’t such bad parents after all. By the time Jesse was born, my brother was introducing Kate as my “wife” at his wedding. Three days after Multnomah County began issuing marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples, Kate and I got up early and drove the two hours to Portland. By ten o’clock, the crowd outside the county building wound around two corners. We took our place at the end of the line and watched it grow behind us. At first, everyone stood solemnly, umbrellas bumping, with slightly stunned looks on our faces. I kept waiting for some government official to step out of a black limousine with a bullhorn and put a stop to it all. People exchanged timid, incredulous smiles, and the line inched forward. Volunteers handed out coffee, granola bars, and daffodils. One young woman offered free Polaroid photos. Another serenaded us with folk songs from the sixties.

Three days after Multnomah County began issuing marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples, Kate and I got up early and drove the two hours to Portland. By ten o’clock, the crowd outside the county building wound around two corners. We took our place at the end of the line and watched it grow behind us. At first, everyone stood solemnly, umbrellas bumping, with slightly stunned looks on our faces. I kept waiting for some government official to step out of a black limousine with a bullhorn and put a stop to it all. People exchanged timid, incredulous smiles, and the line inched forward. Volunteers handed out coffee, granola bars, and daffodils. One young woman offered free Polaroid photos. Another serenaded us with folk songs from the sixties. The couple in front of us huddled together under an umbrella, clutching matching bouquets, lost in their own private cocoon of love and anxiousness. Two women behind us deliberated over whether getting married legally would diminish the vows they’d publicly made seventeen years earlier. Two men held hands and stared forward grimly, as if any distraction might melt their resolve.

The couple in front of us huddled together under an umbrella, clutching matching bouquets, lost in their own private cocoon of love and anxiousness. Two women behind us deliberated over whether getting married legally would diminish the vows they’d publicly made seventeen years earlier. Two men held hands and stared forward grimly, as if any distraction might melt their resolve. It took two hours to get to the front door, then another hour to snake through aisles in the commissioners’ meeting room, like kids queued for the Matterhorn. But nobody seemed to mind. Kate and I leaned against each other, kissed when we wanted, chatted with our linemates, who were beginning to feel like old friends.

It took two hours to get to the front door, then another hour to snake through aisles in the commissioners’ meeting room, like kids queued for the Matterhorn. But nobody seemed to mind. Kate and I leaned against each other, kissed when we wanted, chatted with our linemates, who were beginning to feel like old friends.  The line to get into the auditorium coiled up three flights of stairs. Eager to please my bride, I left Kate standing with the framed photo of our sons she’d insisted on bringing with us and went in search of a flower shop. A florist two blocks away wolfed down pizza while building rows of arrangements. “Sure, it’s great for business,” he said. “But it’s so much more than that. This is like the civil rights movement in the South meets the Summer of Love in San Francisco. This is history.”

The line to get into the auditorium coiled up three flights of stairs. Eager to please my bride, I left Kate standing with the framed photo of our sons she’d insisted on bringing with us and went in search of a flower shop. A florist two blocks away wolfed down pizza while building rows of arrangements. “Sure, it’s great for business,” he said. “But it’s so much more than that. This is like the civil rights movement in the South meets the Summer of Love in San Francisco. This is history.” We used the standard vows passed out by volunteers. “Before these witnesses, I vow to love and care for you as long as we both shall live. I take you, with all your faults and strengths, as I offer myself to you with my faults and strengths. I promise to help you when you need help, and to turn to you when I need help. I choose you as the person with whom I will spend my life.” We watched Daniel and Matt pledge their commitment to each other, and then we pledged ours. I tried not to stammer. Kate tried not to cry. We exchanged the rings we’d taken off that morning, ones we’d had made for our fifth anniversary, seventeen years ago. We kissed. And there we were. Married.

We used the standard vows passed out by volunteers. “Before these witnesses, I vow to love and care for you as long as we both shall live. I take you, with all your faults and strengths, as I offer myself to you with my faults and strengths. I promise to help you when you need help, and to turn to you when I need help. I choose you as the person with whom I will spend my life.” We watched Daniel and Matt pledge their commitment to each other, and then we pledged ours. I tried not to stammer. Kate tried not to cry. We exchanged the rings we’d taken off that morning, ones we’d had made for our fifth anniversary, seventeen years ago. We kissed. And there we were. Married. We stayed overnight at the Paramount Hotel. Had sushi in the bar and champagne in our room. We regaled in our new status and practiced calling each other wife without the quotes. When Kate and I walked around downtown the next morning, I didn’t hesitate to take her hand, and I didn’t let it go when others approached. Not out of defiance, but unhindered celebration. Pure joy. And the whole city seemed to be feeling it. Photos of gay and lesbian couples splashed every front page on the newsstand. People smiled at us as we passed. A young guy with a crew cut chirped, “’Morning!” A man called out “Congratulations” from a balcony while we soaped Just Married on our car windows. When we got home, there were flowers from family, hugs from neighbors, Mazal Tovs from friends, and a rainbow cake with two bride figures.

We stayed overnight at the Paramount Hotel. Had sushi in the bar and champagne in our room. We regaled in our new status and practiced calling each other wife without the quotes. When Kate and I walked around downtown the next morning, I didn’t hesitate to take her hand, and I didn’t let it go when others approached. Not out of defiance, but unhindered celebration. Pure joy. And the whole city seemed to be feeling it. Photos of gay and lesbian couples splashed every front page on the newsstand. People smiled at us as we passed. A young guy with a crew cut chirped, “’Morning!” A man called out “Congratulations” from a balcony while we soaped Just Married on our car windows. When we got home, there were flowers from family, hugs from neighbors, Mazal Tovs from friends, and a rainbow cake with two bride figures. The next week, riding the high, Kate and I strode into the benefits department of the Catholic hospital she works for. At last we had that prized document they’d insisted on for spousal insurance. But it didn’t fly. They were waiting, they said, to see what the courts concluded before deciding how to proceed. With the same pretext, the local newspaper refused to print the announcement and photo I sent. No sense in changing policies for documents likely to be deemed worthless.

The next week, riding the high, Kate and I strode into the benefits department of the Catholic hospital she works for. At last we had that prized document they’d insisted on for spousal insurance. But it didn’t fly. They were waiting, they said, to see what the courts concluded before deciding how to proceed. With the same pretext, the local newspaper refused to print the announcement and photo I sent. No sense in changing policies for documents likely to be deemed worthless.  We framed our marriage certificate and nailed it over the kitchen sink. It looks legal enough to us: signatures of the county official, the minister, and witnesses. There’s the State of Oregon seal dated 1859 and a drawing of a family in a covered wagon. Okay, maybe it says “groom” under my name, but I can live with that.

We framed our marriage certificate and nailed it over the kitchen sink. It looks legal enough to us: signatures of the county official, the minister, and witnesses. There’s the State of Oregon seal dated 1859 and a drawing of a family in a covered wagon. Okay, maybe it says “groom” under my name, but I can live with that.